The Cult of Consensus: How iNaturalist Betrays the Spirit of Citizen Science

Since 2020, I’ve contributed to iNaturalist in good faith—as a naturalist, an ecologist, and someone who values the interconnectedness of all living systems. I joined the platform under the impression that it would amplify local knowledge and expand our collective understanding of biodiversity. What I found instead was an interface-driven cult of consensus, a pseudo-scientific social network that rewards conformity, punishes dissent, and reduces ecological nuance to a performative game of speed and status.

What iNaturalist claims to be—a tool for empowering citizen science—is undermined at every level by its design and its community culture. The system rewards rapid identifications, not accurate ones. It favors the loudest and most active users, not the most qualified. Worse, it has cultivated a kind of gamified vigilantism where users—often with little to no ecological literacy—compete to override identifications made by those with field expertise. The result is an administrative oligarchy masquerading as a crowd, with moderation policies designed to protect the illusion of objectivity while ensuring that anyone who refuses to conform is either shadowbanned, silenced, or shamed into leaving.

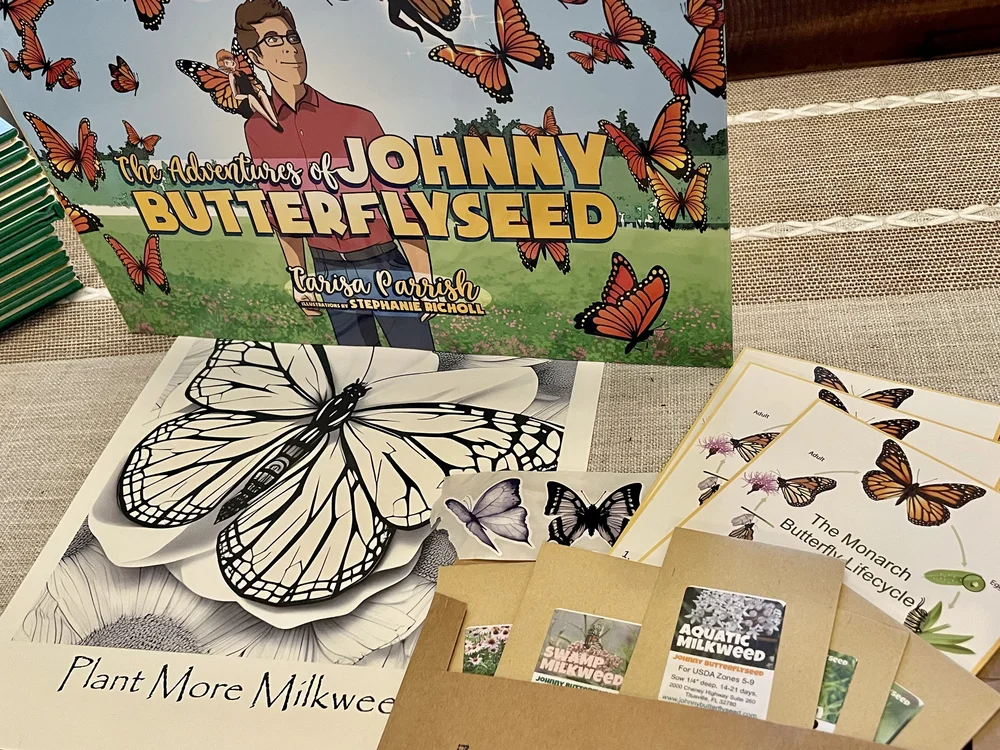

Monarch Butterfly Mission Kit

Your complete habitat starter — including 10 native seed packs, a children’s book, coloring page, lifecycle cards, and stickers. Everything needed to create a pollinator oasis and inspire young stewards. $60, shipping included.

Be a Monarch hero. Plant hope today.

In theory, iNaturalist is a democratic platform where anyone can contribute their observations and insights. In practice, it functions more like a Silicon Valley social experiment in behavioral control. The badge systems, “research grade” thresholds, and top contributor leaderboards create a warped incentive structure that treats the natural world as a source of points and prestige. Identifications are often made in seconds, confirmed by unqualified users, and then locked into place by the “community consensus” algorithm—even when they are wrong. Once an ID hits “research grade,” challenging it becomes an uphill battle, regardless of how sloppy or speculative it was to begin with.

This is not citizen science. This is scientized social media—where the appearance of collaboration masks a deep hostility to actual inquiry.

The problem is compounded by iNaturalist’s administration, which behaves less like stewards of an open scientific community and more like moderators of a reputation economy. Their forums are notoriously hostile to critique, their decisions opaque, and their loyalties aligned with high-volume users who game the system under the guise of productivity. Expertise—genuine, field-tested expertise—is routinely dismissed as arrogance if it deviates from the dominant consensus. If you point out taxonomic ambiguity, local variation, or ecological interdependencies that don’t fit neatly into the drop-down menu, you’re treated as a troublemaker, not a contributor.

And this should surprise no one, because iNaturalist is yet another product of the California technocratic worldview—a world in which data is king, software is sovereign, and community means obedience. Like so many platforms incubated in Silicon Valley, iNaturalist was built not to foster deep understanding, but to instrument and scale the process of identification. What it delivers is not truth, but consensus. Not knowledge, but conformity. Not science, but a performance of science—optimized for engagement, governed by metrics, and hostile to ambiguity.

True ecological literacy resists simplification. It requires immersion, patience, and humility. It thrives on doubt, irregularity, and the kind of contextual awareness that can’t be captured in a square-cropped image with a GPS tag. The natural world is not a dataset. And citizen science, if it is to mean anything at all, must begin with the willingness to stand in contradiction to dominant systems when they get it wrong.

If iNaturalist were serious about science, it would welcome dissent. It would elevate underrepresented knowledge and slow down the process of identification to prioritize accuracy over volume. It would rethink its interfaces to encourage conversation, not scoreboard-driven override behavior. But it will not do this—because it was not built to serve the land or the people who know it. It was built to serve the abstraction of biodiversity, flattened into data points, manipulated for metrics, and sold as progress.

I no longer contribute to iNaturalist as I once did, because I do not consent to be a cog in its epistemic machinery. I do not mistake consensus for truth. And I reject the notion that science must be socialized through points, popularity, or bureaucratic obedience.

Nature is not a leaderboard.

And if we are serious about learning from it, we need platforms—and communities—that respect not just observation, but divergence.