II. Fedegoso or Wild Heliotrope Association

Early in the occupancy of the station at Simla, we selected the family of moths, Euchromidae, for particular study. Among the considerations which prompted this were intricate instincts of the larvae, day-flying habits of many of the adults and the frequency of apparent mimicry.

During the first season, from December, 1952 to May, 1953, our collecting was restricted to three methods: pursuit, in the field, of free-flying moths; the capture of those which alighted on the laboratory screens in the daytime; and capture of the nocturnal forms that came to an illuminated sheet. All this was revolutionized the following season by the use of the common weed, Heliotropium indicum Linnaeus, which proved to be a remarkably efficient and selective attractant. Our attention was directed to this phenomenon by the notes of G. Hagmann (1938) and A. Miles Moss (1947). Our cultivated garden heliotrope is derived from the South American wild species, Heliotropium peruvianum Linnaeus, and is characterized by the clustered appearance of the blossoms, and their strong, sweet, vanilla-like scent.

The Indian heliotrope, Heliotropium indicum, was named by Linnaeus 202 years ago. It has spread from its native home in Asia, and has been acclimated in the New World to such a degree that its present distribution extends from Virginia and Illinois south through Central and South America to Buenos Aires. It has received many common names, the one we have chosen being “fedegoso,” although this introduces a semantic misunderstanding. This is a Portuguese word meaning ill-smelling, whereas Hagmann characterizes it as “exquisite.” To our senses the dry foliage of the heliotrope gives forth a not-unpleasant, somewhat pungent, musty smell, such as might distinguish a longused herbarium. Other names, such as eyebright, refer to alleged curative properties. Still other terms, cocks-comb and scorpion plant, relate to the shape of the flower spike.

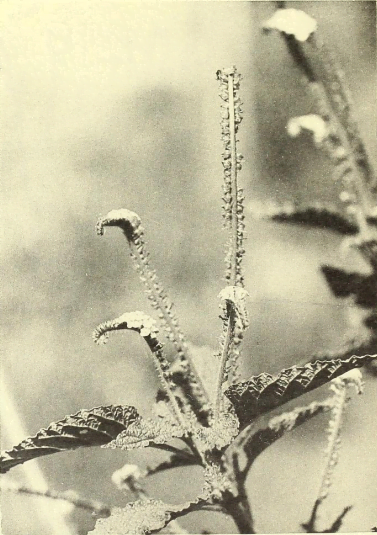

Shortly after our return to Simla, on December 24, 1953, Research Assistant Rosemary Kenedy located a plant of the fedegoso with the assistance of the Botany Department of the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture. From then on, assiduous search revealed many scattered clumps of this plant. It grows in waste places, such as old, neglected gardens and fields, usually singly or in small clumps. It is a typical weed, wholly undistinguished, without intensive odor or color. This wild heliotrope is a small plant, from one to four feet in height, with single, curved spikes of small, pale lilac blossoms. These spikes or racemes are often divided longitudinally into thirds; the terminal third with unopened buds, the middle of full-blown flowers, and the basal third of developing seeds. The stems are hairy, the branches coarse, the leaves large, and oval or ovate. The roots are short and thick and have only a comparatively slight hold on the soil.

In our use of the weed, uprooting is the first step. A half dozen plants are pulled up and shaken free of soil. At Simla the roots are tied together with twine and the cluster is suspended upside-down from some low branch or from a stake driven into the ground. A favorite place is along an open trail through the jungle or in an area free of vegetation close to the forest’s edge. The leaves shrivel soon after the plant is collected and lose whatever of apparent symmetry or character they may have possessed. During subsequent days of sun and rain the foliage becomes in succession dry and brittle, saturated and sodden.

For the first two or three days little activity is observed around the withered plants. Then one, two, a dozen butterflies and moths appear, coming upwind, and all alight. The desiccated racemes of flowers and seeds seem to exert especial attraction, but the stems, leaves and roots are far from neglected.

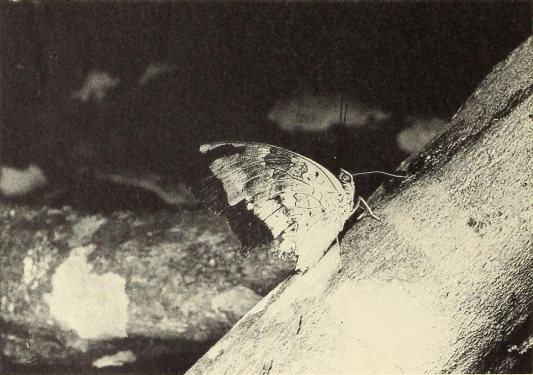

The dominating point of interest in fedegoso, as an attractant, is its selective quality. In the course of five months of observation in and around Simla, we detected members of only four families of Lepidoptera coming to the bunches of dead plants. Two of these were butterflies, Danaidae and Ithomiidae, and two were moths, Euchromidae and Arctiidae. Other groups, such as heliconids, nymphalids and pierids, sometimes flew past the dry vegetation, but no individual ever alighted or even hesitated. Added to this is the fact that in most classifications the four selected families are placed at the top of their respective groups, presumably indicating extreme specialization in the scale of lepidopteran phylogeny.

This remarkable, selective, attractant phenomenon was reaffirmed during a few weeks of our experience with fedegoso in Surinam, and in reports from Para, of Hagmann and Moss.

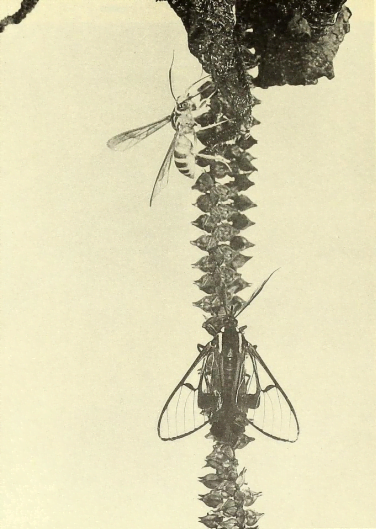

The selective quality of fedegoso is apparent in other than lepidopteran families. Details of specific selection as shown in Euchromidae will be discussed in future papers. One example will suffice here. Until we began to use this method of collecting we had never come across a specimen of Sphecosoma trinitatis Rothschild, a close mimic of a small Polybia wasp. The resemblance is so exact that only close examination reveals the difference between moth and wasp. In the course of five months we took or observed one hundred and forty-seven of these wasp-mimicking moths on fedegoso, and these resolved into three distinct species, two of which had not heretofore been recorded from Trinidad.

Arctiidae was the only other family of moths attracted by fedegoso, and this sparsely, as only fourteen specimens of seven species were taken, three of which were uniques.

As euchromids were the dominant fedegoso group among moths, so ithomiids were, far and away, the more numerous of the butterflies. Fifteen species of Ithomiidae have been recorded from Trinidad. Of these, on March 21, 1954, at 8 A.M., on two adjacent bunches of fedegoso, I observed or collected eight species, totalling a minimum of 257 individuals. The shade-loving, skeleton-winged species Ithomia drymo pellucida Weymer and Hymenitis andromica trifenestra (Fox) excelled in numbers, comprising three-fourths of the total ithomiids.